Too Big To Fail: Zack Snyder’s JUSTICE LEAGUE and the history of juggernaut Hollywood productions

Every generation has one, an enormous, expensive tentpole release with its own gravitational pull. A journey from conception to completion so twisted and punishing for all involved that the production itself becomes its own voyage of the damned, and the objective quality of the final product becomes almost a non-issue.

Zack Snyder’s Justice League, making its debut on HBO MAX this month, is hard-pressed to find a rival to that honor even in an age where superheroes dominate the box office. With the amount of time, money, and resources that Warner Bros. has shoveled into this operation, even and especially in light of the DCEU’s inconsistent track record, one can only conclude that the act of taking these costumed strongmen from the funny pages and translating them to film is enough to drive men mad.

The rising hype around the streaming premiere invites comparisons from Hollywood’s past for what has become the big-screen clusterf*ck of our age. My own thoughts on Zack Snyder’s vision of DC’s flagship superteam have fluctuated over time, as the fabled “Snyder Cut” evolved from the theoretical to the actual.

And with the 4-hour cut of Snyder’s trilogy-capper now upon us, it’s a good time to look back at how Zack and his League stack up in the pantheon of record-smashing motion picture mismanagement and unchecked artistic hubris.

CLEOPATRA (1963), dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz

“In the movie business, and particularly then, naivete and compulsive behavior were the order of the day, and the inmates ran the asylum. And so, we never gave up on an obsession, because we were fueled by the idea that every obsession makes money.“

--Former Fox exec David Brown, “Cleopatra: The Movie That Changed Hollywood”

Elizabeth Taylor as the titular Queen of Eqypt in CLEOPATRA (1963), 20th Century Fox

Besides other superhero movies, the first point of comparison that came to mind as I observed this expensive hurricane unfold was Cleopatra, released by 20th Century Fox in 1963, the star-studded historical drama chronicling the life and reign of the legendary Queen of Egypt.

These days the film is mostly remembered as the opening salvo in Elizabeth Taylor & Richard Burton’s very public off-screen affair. But that’s just the garnish on a souffle of false starts, a half-finished screenplay, shady bookkeeping, the lead actress almost dying because she was allergic to England, and an entire studio backlot turning into a ghost town.

The brainchild of veteran producer Walter Wanger in 1958, 20th Century Fox first attempted the epic production in the UK under director Rouben Mamoulian, starting with a budget of $5 million. One of those millions went straight to Elizabeth Taylor’s contract, becoming the first actor ever to be paid seven figures for a single role.

But filming halted when Taylor became deathly ill. The filmmakers shot as much as they could without their title character, but the production eventually unraveled after 16 weeks and $7 million spent, with only ten minutes of usable film to show for it. Rather than take their insurance reimbursement and head for greener pastures, Wanger and Fox president Spyros Skouras chose to ante up for another round.

Taylor got contractual approval for director, and elected Suddenly Last Summer’s Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who signed on to write AND direct. Peter Finch and Stephen Boyd had to bow out as Caesar and Antony, and so Rex Harrison and Richard Burton were cast. Since England’s weather had taken its toll on both the lead actress and the expensive sets, they moved the production to Cinecitta Studios outside Rome, Italy. Much like in England, building the sets was such a project that it caused a country-wide shortage of building materials.

By the time shooting was set to commence, they were running $70,000 a day ($3 million higher than Ben Hur). Skouras worked to hide the costs from the shareholders so they wouldn’t merge into a gestalt monster and devour him. When the accountant refused to make the budget appear smaller, he was fired and Skouras hired one who would.

And best of all, Mankiewicz was only halfway finished with the script, but they had to begin shooting before contracts went into overtime. So as writer and director, Mank spent every spare moment working on the rest of the script, including between takes. And because they were filming a half-finished script, they had to shoot the scenes in order rather than for efficiency, which meant the whole cast and crew had to be on hand for much of the shoot.

Marc Antony (Richard Burton) and Queen Cleopatra (Elizabeth Taylor), 20th Century Fox

By the end of 1961, Mank was taking shots of stimulants in the morning and a sedative to go to sleep to get through the ordeal, but the production had reached a decent clip with half the film shot, the dailies looking good, and the rest of the script ready to go. It was around this time that the love story began.

The electrifying onscreen chemistry of Cleopatra and Marc Antony gave way to Taylor and Burton’s scandalous off-screen romance, which has since become its own Hollywood legend. Both married to other people at the time, the affair became such talk of the town and tabloids that it eventually bled into the film’s marketing.

Meanwhile, 20th Century Fox had to shut down for 4 months and take everyone off payroll, dedicating all their attention to the production of this single epic. In a bid for cash, the studio sold a 180-acre backlot to developers, resulting in the creation of what is now Studio City.

On the other side of the lot, former Fox president Daryl F. Zanuck was hard at work producing his D-Day epic The Longest Day, the only other film not shut down by Cleopatra. To ensure that his project would be completed properly, Zanuck stormed the board’s quarterly meeting and seized control of the studio he had helped create.

Once Cleopatra had wrapped principle photography, the studio was a ghost town. One of Zanuck’s first actions was to fire Mankiewicz and oversee the edit himself. This backfired instantly, since much of the film had been shot without a completed shooting script, so the only way to make sense of the mess was to hire Mankiewicz back into the editing room and call a truce.

Mank’s original cut was 6 hours long; he tried to convince the studio to release it as two films, one for Cleo & Caesar, the other with Cleo & Antony, to be released separately. But he was overruled and the film was instead trimmed down to a single 3-hour theatrical release.

Cleopatra was the most successful release of 1963, but no amount of ticket sales could feasibly recoup the cost of production. With a final price tag of $31 million (in 1960s money), it was the most expensive movie ever produced, and signaled the end of an era for Hollywood big-budget epics.

Under Zanuck’s management, a series of mid-budget hits helped them get back into the black. In the aftermath, studio structure and finances across the showbiz landscape were reorganized to hopefully ensure that no single movie could ever again drive a studio to bankruptcy.

HEAVEN’S GATE (1980), dir. Michael Cimino

“The lore of Heaven’s Gate is don’t make a movie like that, because it’ll finish you off. The lore of Heaven’s Gate is disaster.”

--Christopher Mankiewicz (son of Joseph L.), “Final Cut: The Making & Unmaking of Heaven’s Gate”

Kris Kristofferson as James Averill in HEAVEN’S GATE (1980). United Artists

Hot off the towering success of his star-studded Vietnam War drama The Deer Hunter, 1980 saw the release of auteur director Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate.

Given carte blanche by United Artists with only his third feature film, Cimino zeroed in on the story of the Johnson County War, a conflict in 1890s Wyoming between the area’s poverty-stricken immigrants and wealthy cattle farmers. Principal photography commenced just a week after The Deer Hunter walked away with the top prizes at the Oscars.

Rather than poor planning, weather problems, or disputes among the cast (as some of the trades at the time reported), the production’s mushrooming scale was almost entirely the result of Cimino’s fanatical attention-to-detail, with studio execs caving to the director’s demands virtually every step of the way.

The film’s original budget ballooned by 400% from its initial projection (topping out at $44 million), while principle photography in Montana ran 200 days over the originally scheduled 69-day shoot. Cimino seemingly embraced every artistic excess imaginable.

In the film’s many crowd scenes, Cimino spent hours and hours on the precise placement of every extra. Some scenes took upwards of 40 or 50 takes before the director was satisfied. An entire town exterior set was torn down and rebuilt because Cimino wanted the street a little wider. A horse-drawn buggy driven by Jeff Bridges’ character was shipped to multiple builders to ensure every single piece was authentic to the time period. Actor John Hurt had so little to do throughout the shoot, he was able to film his lead role in The Elephant Man on the side. There were accusations from the American Humane Association of actual cockfights, decapitated chickens, and a group of cows disemboweled to provide "fake intestines" for the actors.

The executives at United Artists discussed firing Cimino, but their efforts to rein in the auteur came approximately 1.3 million feet of film too late. After a grueling summer of post-production, during which Cimino reportedly locked execs out of the editing room, the first cut screened for the studio was over 5 hours; the climactic battle scene between the settlers and the US Army was practically its own movie.

With a final runtime of 219 minutes, the film made its premiere in New York City on November 18, 1980.

Critics were merciless. The compelling story ripped from the history books got drowned out by hours of overextended scenes, crowd shots, dancing sequences, and pretty scenery. Vincent Canby of the New York Times famously compared it to “a forced four-hour walking tour of one’s own living room.”

After a one week run in New York, Cimino convinced United Artists to pull it from cinemas so that he could cut it down to a more presentable 149-minute runtime, which saw its wide release the following April. But by then the damage was done. After spending $44 million to produce and release, ticket sales for Heaven’s Gate brought in just $1.3 million.

With the film’s troubled release, we can see the reverse of what would become the lucrative “director’s cut” timeline, where the unfiltered vision lands with a thud, leaving the filmmakers in a scramble to put forth something that won’t bore their audience to tears. In fact, when the 219-minute cut was broadcast on Z Channel in 1982, it was the first time that the term “director’s cut” was presented as such.

Although Heaven’s Gate has received something of a reappraisal over the years, very few box office bombs can claim to have sunk a studio. Even though the film’s poor box office was little more than a stock market hiccup to the studio’s parent company TransAmerica, they still saw fit to sell United Artists to MGM.

The whole debacle almost single-handedly ended the Hollywood auteur movement that defined the 1970s, where young visionary filmmakers were given blank checks to create magnificent epics, and it turned Cimino’s meteoric rise in the industry into a cautionary tale.

Which brings us back to...

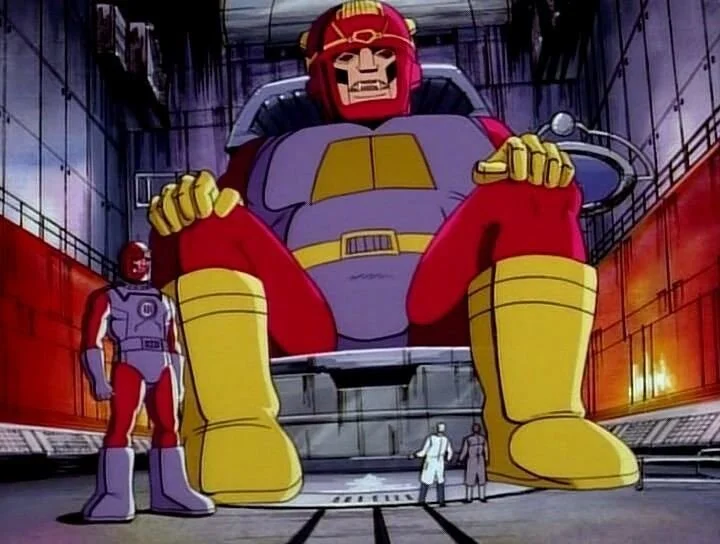

JUSTICE LEAGUE (2017) & Zack Snyder’s JUSTICE LEAGUE (2021)

Snyder on set of JUSTICE LEAGUE with Ben Affleck and Gal Gadot

Many of us know the story by now, whether we want to or not.

Man of Steel may not have set the world on fire to the degree that the Dark Knight trilogy had, but Zack Snyder nonetheless got the go-ahead from Warner Bros. and DC for an ambitious multi-film storyline to rival Disney/Marvel’s burgeoning cinematic offerings.

Promising to distill iconic storylines from The Death of Superman to The Dark Knight Returns, landmark comics that had helped elevate the DC brand both financially and artistically a generation before, all eyes were on Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice as the first major motion picture to feature both heroes on the big screen (plus Wonder Woman). After pitting their flagship titans against each other for a blockbusting grudge match, the story would continue in the ultimate team-up of the ultimate team of heroes against the ultimate bad guy of bad guys in the sure-to-be universe-exploding culmination, with the promise of even more spin-offs and sequels if all went to plan.

Things did not so much go to plan. The WB studio execs were already nervous after the tepid response to the grimdark antics of BvS upon its March 2016 release. While audiences responded more favorably than critics, BvS saw over 50% box office drop in its second week, and no assurances about the thematic richness of the “Martha” scene could turn it around.

But in the wake of a family tragedy, Snyder chose to step away from Justice League during post-production in May 2017. Warner Bros., already working to course-correct, brought on Joss Whedon, fresh off of Marvel’s Avengers: Age of Ultron, to reshoot large chunks of the film to accelerate the “hope and optimism” and include more jokes. (David Ayers’ Suicide Squad faced similar cutting-room revisions a year earlier.)

Whedon’s reshoots vs. Snyder’s original

More recently, allegations of unprofessional on-set behavior by Whedon, plus producers Geoff Johns and Jon Berg, first brought to light by Cyborg actor Ray Fisher, have cast an extra cloud of scandal over an already deeply troubled production.

The theatrical cut of Justice League was released to cinemas on November 17, 2017 to mixed reviews and earned less than $100 million its opening weekend. The final worldwide gross was around $650 million, even less than what Man of Steel earned, off of a significantly higher production budget. While the 2-hour Whedon cut maintained the basic framework of what had been originally planned under Snyder, it was widely understood by critics and audiences to be a compromised vision, with Henry Cavill’s CG-smooth facial hair becoming an instant meme.

It didn’t take long for fans to launch a barrage of online petitions, billboards, airplane banners, all under the hashtag #ReleasetheSnyderCut. Snyder himself poured fuel on the fire by joining the chorus, and even the cast jumped on board in support. Even though there was no expectation (not even from the director) that Snyder’s version existed as anything other than a collection of unfinished scenes and FX shots, the hype surrounding the many deleted and discarded story elements soon eclipsed any interest in the theatrical film’s watered-down plot.

For industry insiders, the idea of Warner Bros. shelling out even more cash to complete seemed like little more than a pipedream. That is, until HBO Max came along, offering an ideal venue for WB’s new management to put the full breadth of Snyder’s original vision on screen in the hopes of driving subscribers to their new streaming platform.

The team assembled in ZACK SNYDER’S JUSTICE LEAGUE on HBO MAX

The reported cost of the reshoots/post-production required to assemble the Snyder Cut ($70 million) was more than the entire production budget of Jurassic Park ($63 million) not adjusted for inflation.

After almost 5 years of second guessing and hand wringing, with no small amount of fans harassing the studio into correcting this slight against a director that they had once bet the farm on before trying to welch, the culmination of Zack Snyder’s contractually promised magnum opus may now set sail in all it’s high-contrast, black-suited, 4:3 glory.

It’s not as though Warner Bros. stopped making movies (or DC movies) in that time, but even with Aquaman and Shazam lighting up the box office in JL’s aftermath (plus the long-delayed Wonder Woman 1984 released to streaming in the meantime), the future of the rest of the team, particularly Superman, the Flash, and Cyborg, are still up in the air. Justice League 2 currently has no release date.

While the shareholders seem to get nervous over anything that doesn't have “Harry Potter” or “Dark Knight” in the title, Warner Bros. was in no danger of going under as a result of their missteps surrounding the DCEU. In fact, it’s likely thanks to past foul-ups like Heaven’s Gate and Cleopatra that Warner Bros. was able to not only continue making stupidly large tentpole films post-Justice League without missing a step, but continue making movies in the same franchise.

The buzz going into Snyder’s Justice League is largely positive, even among fans and reviewers that were wary of his schtick since Man of Steel. And even if Snyder’s 4-hour cut is more of a chore to sit through than the theatrical release, its scale is far more reflective of the time, money, and manpower that went into producing it.

As much as the studio longs to replicate Marvel’s success (or create counter-programming to it), Warner Bros. knew what they were getting with Snyder. They made a commitment to his singular vision for their costumed IPs, and box office returns or critical reception be damned, it seems they cannot truly move forward until they’ve made peace with that vision.

Snyder had put forth plans for future JL sequels in his original pitch. But now after this whole ordeal, he says he’s done making DC movies, so that may be that. And while helming a 10-hour superhero trilogy is more than most directors are allowed to accomplish in a lifetime, the fans who rallied to #ReleasetheSnyderCut may still disagree as to whether the studio’s debt to Snyder should include future DC movies.

And that’s even if the final product is actually good.